Treatments

Rheumatoid arthritis is characterized by articular inflammation, synovial joint damage and increasing disability over time. In addition, individuals who suffer from RA are at increased risk of cardiovascular morbidity, cancer, and osteoporosis. With clinical evidence supporting the use of stringent disease control measures to improve patient outcomes, disease-modifying antirheumatic agents (DMARDs) have become the mainstay of RA treatment. Newer agents provide relief of signs and symptoms, reduce impairment of physical function and QOL, and inhibit structural damage to cartilage and bone.

Early diagnosis and treatment of rheumatoid arthritis can prevent or substantially slow progression of joint damage in 90% of patients. Through continual monitoring of disease activity and the use of DMARDs, the treatment goal of RA is remission or low disease activity within 6 months. A treat-to-target strategy aimed at reducing disease activity by at least 50% within 3 months and achieving remission or low disease activity within 6 months can prevent RA-related disability. Approximately 40%-50% of patients achieve remission or low disease activity with an initial therapy of methotrexate in combination with glucocorticoids. For patients that fail initial therapy with methotrexate, novel targeted therapies, such as Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors or tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors, in combination with methotrexate have allowed up to 75% of these patients to reach their treatment goal.1

Treating-to-Target

In 2010, the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) issued new clinical classification criteria for RA, with the goal of codifying a strategy to identify patients who would benefit from early, effective treatment to prevent later-stage disease.2

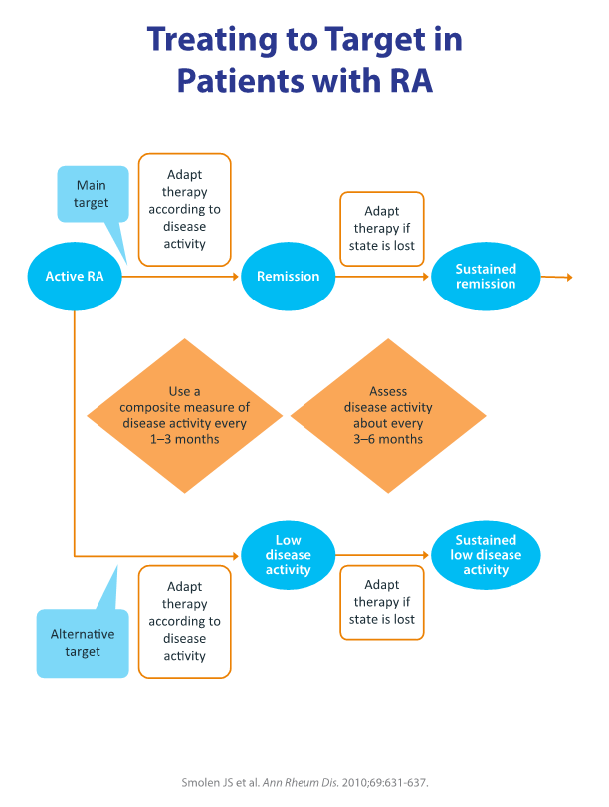

Using these new criteria, a treatment paradigm called treat-to-target (T2T) has been proposed that encourages tight control. T2T utilizes composite measures of disease activity and health-related quality of life, with the appropriate switching of agents (figure 1). Goals of therapy according to T2T are to achieve and maintain a patient’s function and to obtain clinical remission, defined as the absence of signs and symptoms of significant inflammatory disease.3 Low disease activity may be an acceptable treatment goal, particularly in patients with long-standing established disease.3 Other recommendations are to measure disease activity as needed, adjust dosage and medication regimens to meet targets, and share treatment decisions between physicians and patients, including patients’ lifestyle choices and comorbidities in the decision process.3

The T2T paradigm is supported by strong clinical evidence for both early and established disease, and it is now included in several recommendations for the management of RA.4 However, exactly how rheumatologists’ and patients’ behaviors play a role in the implementation of T2T in clinical practice is currently under investigation.

Figure 1.2

Therapeutics for RA

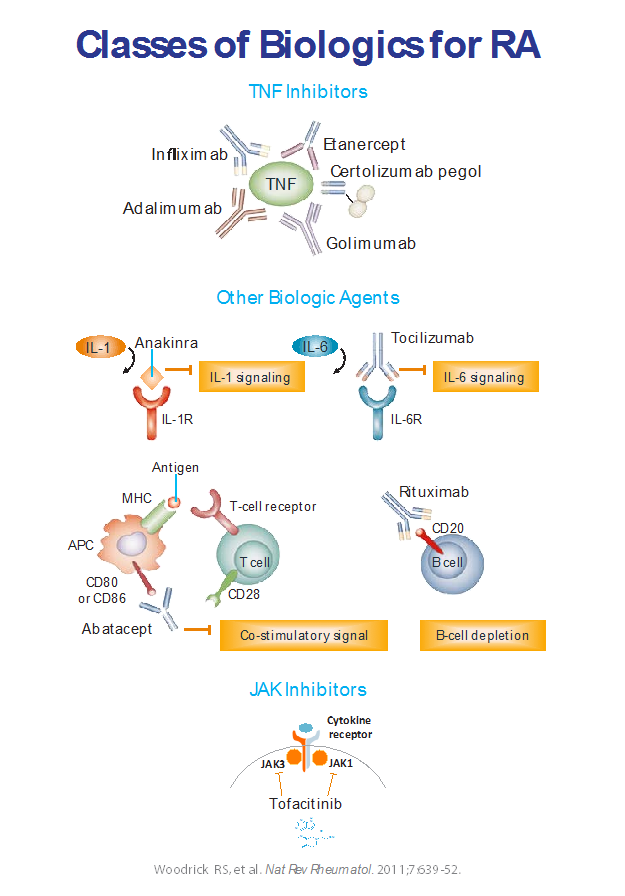

Conventional treatment options for RA include synthetic DMARDs (hydroxychloroquine, leflunomide, sulfasalazine, and methotrexate [MTX]), non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs, glucocorticoids, and non-pharmacological measures, such as physical, occupational, and psychological approaches. MTX is considered the “anchor” DMARD because of extensive positive clinical experience. However, MTX toxicity can limit its use, and many patients do not respond adequately to MTX alone. Advances in the understanding of the pathophysiology of RA have led to the development of several biological DMARDs and small-molecule inhibitors of cytokine signaling, adding to existing options (figure 2). 4

FDA-approved agents for MTX-inadequate responders or patients who are intolerant to MTX currently include:

- Interleukin-1 (IL-1) receptor antagonist—anakinra

- Monoclonal antibodies against tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α—infliximab, etanercept, adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, and golimumab

- Monoclonal antibodies against IL-6 receptor—tocilizumab, sarilumab

- Cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4-immunoglobulin G1 (CTLA-4- IgG1) fusion protein (blocker of T-cell co-stimulation)—abatacept

- JAK (Janus kinase) tyrosine-kinase inhibitors—tofacitinib, baricitinib, and upadacitinib

- Agents that are FDA approved for TNF-inadequate responders include the monoclonal antibody against CD20—rituximab.

Figure 2.4

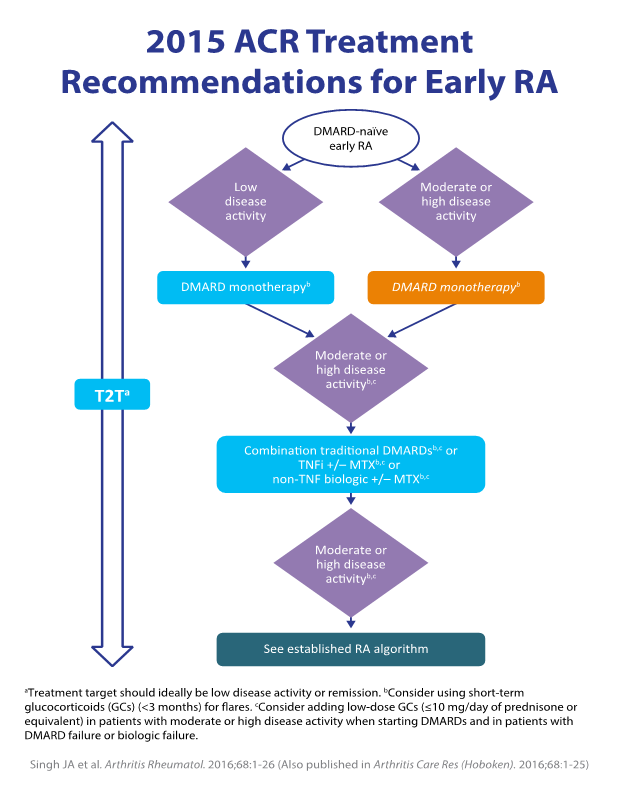

The broad range of agents, administration routes (including new oral agents), and mechanisms of action enhance clinical opportunities. Evidence-based guidelines have been developed, and updated recommendations are released periodically based on new clinical evidence (figure 3). The supporting research includes head-to head comparative trials of treatment regimens for different RA patient populations.6

Figure 3.5

Clinical Trial Data

Methotrexate is preferred as initial therapy for RA. However, for patients who do not respond adequately to methotrexate monotherapy, the addition of a biological DMARD or JAK inhibitor is recommended. Clinical trial data supporting the use of different agents is summarized below.

Biological DMARDS

Several recent trials have investigated the efficacy of biological DMARDs (bDMARDs) in monotherapy and in combination. There is evidence to suggest that the combination of a biological DMARD and a conventional DMARD (cDMARD) is more effective than a cDMARD alone.

- The C-EARLY study found a significantly higher proportion of DMARD-naïve patients sustained Disease Activity Score using a 28 joint count (DAS28) less than 2.6 between weeks 40 and 52 on combination certolizumab pegol and methotrexate (MTX) versus MTX alone (29% vs 15%).7 Similar results were found in MTX-naïve patients in the C-OPERA trial.8

- In the BREVACTA study, patients who failed a previous DMARD therapy had a significant improvement in ACR20 responses with subcutaneous tocilizumab plus methotrexate versus background MTX after 24 weeks (61% vs 32%).9

- In the CARDERA-2 trial, combination anakinra and MTX therapy did not significantly reduce radiological disease progression over MTX monotherapy.10

Clinical trial data suggests that the combination of a bDMARD and csDMARD is more effective than bDMARD monotherapy.

- In the RA AVERT study, MTX-naïve patients achieved a DAS28 <2.6 more often with abatacept-methotrexate combination therapy than with MTX monotherapy or abatacept monotherapy at 12 months (60.9% vs 45.2% vs 42.5%).11

- The results of the FUNCTION study showed higher proportions of patients with DAS remission and ACR responses with tocilizumab 8mg/kg plus MTX than with tocilizumab monotherapy.12,13

- The SURPRISE study showed that a status of DAS28 <2.6 at week 24 was more often achieved in RA patients with inadequate response to MTX when tocilizumab was added to MTX therapy than when the patient was switched from MTX to tocilizumab (70% vs 55%). This benefit disappeared at week 52 (72% vs 70%). Radiographic progression was significantly lower with combination therapy than with tocilizumab monotherapy.14

In a systematic review of 26 studies, investigators compared the safety of bDMARDs to cDMARDs.15

- Overall, a significantly increased risk of serious infections was found in users of bDMARDs, with an adjusted hazard ratio between 1.0 and 1.8 per study. This association was not found in more recent studies.

- Most studies did not show an increased occurrence of herpes zoster in patients receiving TNF inhibitors.

- Studies investigating the risk of tuberculosis found a significant increase in the risk of tuberculosis in patients on TNF inhibitors compared with the general population and patients on cDMARDs (aHR of 2.7 to 12.5 per study).

- In general, comparisons of TNFi and non-TNFi bDMARDs did not find a significant difference in the risk of serious infections or herpes zoster between any agents (Ramiro 2016).

- In five of the studies in the systematic review, TNFi use was associated with a higher risk of lymphoma (aHR between 2.3 and 5.9) and non-melanoma skin cancer (aHR: 1.7) than the general population. The risk of lymphoma and non-melanoma was similar for bDMARDs and cDMARDs. One study found an increased risk of melanoma with bDMARDs compared to cDMARDs (aHR 1.5).

Targeted Synthetic DMARDs

Although treatment with biological DMARDs results in disease suppression for many patients, only 30% of patients receiving biological DMARDs achieve complete remission and the majority will experience disease exacerbation following treatment cessation.16,17,18 An additional important consideration is the route of administration. Targeted synthetic DMARDs, such as baricitinib and tofacitinib, and upadacitinib are orally administered, providing a convenient alternative to subcutaneous or intravenous administration of biological DMARDs.19

Tofacitinib is indicated for the treatment of adults with moderate to severe RA who have had an inadequate response to methotrexate. It may be used as monotherapy or in combination with methotrexate or other DMARDs.20 In the ORAL Solo study, patients with an inadequate response to at least one previous DMARD achieved at least a 20% improvement in ACR20 rates after 3 months with either 5 mg or 10 mg of tofacitinib compared to placebo (59.8% vs 65.7% vs 26.7%, respectively).21 Another study showed that tofacitinib in combination with a conventional DMARD significantly improved ACR20 response rates after 6 months in patients with active disease despite prior treatment (52.1% for 5mg tofacitinib, 56.6% for 10 mg tofacitinib, and 30.8% for placebo).22 In a comparison of tofacitinib to the anti-TNF biologic adalimumab in RA patients receiving methotrexate, 6-month ACR20 rates were 51.5% for patients receiving 5 mg tofacitinib, 52.6% for the 10 mg tofacitinib group, 47.2% for the adalimumab group, and 28.3% for those receiving placebo23. Tofacitinib was shown to reduce the signs and symptoms of RA and improve physical functioning relative to methotrexate.24 However, the improvements were significantly greater for patients with early compared to established RA, supporting early diagnosis and treatment of symptoms.25

Baricitinib, a second JAK inhibitor, has been approved for the treatment of adult patients with moderately to severely active rheumatoid arthritis who have had an inadequate response to one or more tumor necrosis factor antagonist therapies.26 Several phase III clinical trials have demonstrated that treatment with once-daily oral baricitinib improved RA symptoms relative to placebo. In the RA-BEACON trial of 527 patients with inadequate response to TNF inhibitors or other biological DMARDs, a significantly higher proportion of patients receiving 4 mg baricitinib had an ACR20 response after 12 weeks compared to those given placebo (55 vs 72%).27 The RA-BUILD study investigated the efficacy and safety of 4 mg baricitinib in 684 biologic-naïve patients who had an inadequate response to conventional DMARDs. Patients treated with baricitinib were more likely to experience an ACR20 response (62% vs 39%) and improvements in disease activity and disability scores at week 12 than patients receiving placebo. Radiographic progression of structural joint damage at week 24 was significantly reduced with baricitinib compared to placebo.28

The results of the RA-BEAM trial demonstrated that baricitinib may significantly improve clinical outcomes compared to adalimumab or placebo in patients with an inadequate response to methotrexate. Of the 487 patients receiving baricitinib, 70% experienced an ACR20 response at 12 weeks, compared with 61% of the 330 patients taking adalimumab and 40% of the 488 patients given placebo.29 A study of long-term use of baricitinib in 3400 patients with moderate to severe RA found that exposure up to 5.5 years was safe and well tolerated. No differences in rates of death, adverse events leading to drug discontinuation, malignancies, major adverse cardiovascular events, or serious infections were seen for 4 mg baricitinib when compared to 2 mg baricitinib or placebo.30

Upadacitinib is the third JAK inhibitor approved by the FDA for use in adults with moderate-to-severe RA with inadequate response or intolerance to methotrexate. The SELECT series of trials enrolled thousands of patients with RA and reported when compared with placebo that an ACR20 improvement was achieved by 71% of patient in the upadacitinib arm compared to 36% in the placebo group31. Upadacitinib was superior to adalimumab based on ACR50 response rates, achievement of a DAS28-CRP score of ≤ 3.2, change in pain severity score, and change in the Health Assessment Questionnaire disability index31.

The US prescribing information for tofacitinib and baricitinib, and upadacitinib warn of the risk of serious infections, including herpes zoster, tuberculosis and other opportunistic infections. The risk of malignancy is similar for JAK inhibitors and biological DMARDs. Prescribing information warns of the potential risk of lymphoma and other malignancies, including lung and breast cancer.20,26

REFERENCES

- Aletaha D, Smolen JS. Diagnosis and management of rheumatoid arthritis: a review. JAMA. 2018;320(13):1360-1372.

- Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ, et al. 2010 rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:2569-2581.

- Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Bijlsma JW, et al. Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:631-637. http://ard.bmj.com/content/early/2010/05/04/ard.2009.126532.full.pdf+html

- Smolen JS. Treat-to-target as an approach in inflammatory arthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2016;28:297-302.

- Singh JA, Saag KG, Bridges SL Jr, et al. 2015 American College of Rheumatology guideline for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:1-26. (Also published in Arthritis Care Res [Hoboken]. 2016;68:1-25.)

http://rheumatology.org/Portals/0/Files/ACR%202015%20RA%20Guideline.pdf - Smolen JS, Landewé R, Breedveld FC, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2013 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:492-509.

http://ard.bmj.com/content/early/2013/10/23/annrheumdis-2013-204573.full.pdf+html - Emery P, Bingham CO, Burmester GR, et al. The first study of certolizumab pegol in combination with methotrexate in DMARD-naive early rheumatoid arthritis patients led to sustained clinical response and inhibition of radiographic progression at 52 weeks: The C-early randomized, double-blind, controlled phase 3 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(Suppl 2):712.

- Atsumi T, Yamamoto K, Takeuchi T, et al. The first double-blind, randomised, parallel-group certolizumab pegol study in methotrexate-naive early rheumatoid arthritis patients with poor prognostic factors, C-OPERA, shows inhibition of radiographic progression. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:75–83.

- Kivitz A, Olech E, Borofsky M, et al. Subcutaneous tocilizumab versus placebo in combination with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2014;66:1653–1661.

- Scott IC, Ibrahim F, Simpson G, et al. A randomised trial evaluating anakinra in early active rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2016;34:88–93.

- Emery P, Burmester GR, Bykerk VP, et al. Evaluating drug-free remission with abatacept in early rheumatoid arthritis: results from the phase 3b, multicenter, randomized, active-controlled AVERT study of 24 months, with a 12-month, double-blind treatment period. Annals of Rheumatic Diseases. 2015;74:19-26.

- Burmester GR, Rigby WF, van Vollenhoven RF, et al. Tocilizumab in early progressive rheumatoid arthritis: FUNCTION, a randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:1081–91.

- Burmester G, Rigby W, Van Vollenhoven RF, et al. Tocilizumab combination therapy or monotherapy or methotrexate monotherapy in methotrexate-naive patients with early rheumatoid arthritis: 2-year clinical and radiographic results from a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(Suppl 10):S811–12.

- Kaneko Y, Atsumi T, Tanaka Y, et al. Comparison of adding tocilizumab to methotrexate with switching to tocilizumab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis with inadequate response to methotrexate: 52-week results from a prospective, randomised, controlled study (SURPRISE study). Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75: 1917–23.

- Ramiro S, Sepriano A, Chatzidionysiou K, et al. Safety of synthetic and biological DMARDs: a systematic literature review informing the 2016 update of the EULAR recommendations for management of rheumatoid arthritis. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2017;76:1101-1136.

- Yamaoka K. Janus kinase inhibitors for rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2016; 32: 29–33.

- Tanaka Y, Hirata S, Saleem B, Emery P. Discontinuation of biologics in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2013; 31: S22–S27.

- van der Heide A, Jacobs J, Bijlsma J, et al. The effectiveness of early treatment with ‘‘second-line’’ antirheumatic drugs. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1996, 124: 699–707.

- Louder A, Singh A, Saverno K, et al. Patient preferences regarding rheumatoid arthritis therapies: a conjoint analysis. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2016; 9: 84–93.

- Xeljanz (tofacitinib) tablets FDA drug approval package. Available at https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2012/203214Orig1s000TOC.cfm [Accessed 24 April 2017].

- Fleischmann R, Kremer J, Cush J, et al. Placebo-controlled trial of tofacitinib monotherapy in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2012; 367: 495–507.

- Kremer J, Li Z, Hall S, et al. Tofacitinib in combination with nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2013; 159: 253–261.

- Van Vollenhoven R, Fleischmann R, Cohen S, et al. Tofacitinib or adalimumab versus placebo in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2012; 367: 508–519.

- Lee EB, Fleischmann R, Hall S, et al. Tofacitinib versus methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2014; 370: 2377–2386.

- Fleischmann R, Huizinga T, Kavanaugh AF, et al. Efficacy of tofacitinib monotherapy in methotrexate-naive patients with early or established rheumatoid arthritis. RMD Open. 2016; 2: e000262.

- Olumiant (baricitinib) package insert. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/2 07924s000lbl.pdf. Accessed January 10, 2019.

- Genovese M, Kremer J, Zamani O, et al. Baricitinib in patients with refractory rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2016; 374: 1243–1252.

- Dougados M, van der Heijde D, Chen Y-C, et al. Baricitinib in patients with inadequate response or intolerance to conventional synthetic DMARDs: results from the RA-BUILD study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017; 76: 88–95.

- Taylor P, Keystone E, van der Heijde D, et al. Baricitinib versus placebo or adalimumab in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2017; 376: 652–662.

- Smolen J, Genovese M, Takeuchi T, et al. Safety Profile of Baricitinib in Patients with Active Rheumatoid Arthritis with over 2 Years Median Time in Treatment. J Rheumatol. 2018 Sep 15. pii: jrheum.171361. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.171361. [Epub ahead of print]

- Fleischmann R, Pangan A, Song I, et al. Upadacitinib versus placebo or adalimumab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to methotrexate : results of a phase III, double-blind, randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019 ; Jul 9 [Epub ahead of print]